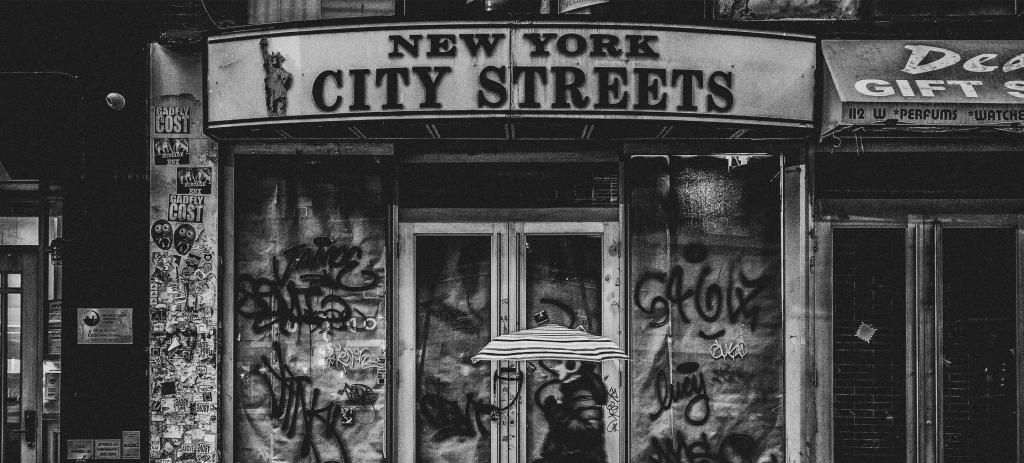

Much like New York City itself, its housing market is unique.

The major differentiator is the ownership structures, specifically co-operatives. While many are familiar with condominiums, co-operatives are likely to be less familiar. The two share similar qualities, but also have defining characteristics that should be understood before deciding between the two.

CONDOMINIUM

When the time comes to sell your home, most owners have a common objective in mind and that is to make the largest profit possible. If this is your objective, you have considered selling on your own to save on brokerage fees.

They are considered real property and are the most straightforward structure. They require a minimum down-payment of 10% of the purchase price and are generally more lenient with their purchase requirements. The purchase process is simple, usually just requiring a completed purchase application. Although highly unusual, condos have the right to exercise their “right of first refusal” or their option to buy the unit out from under a potential buyer with the same agreed upon terms as the initial deal.

There is a board of directors who are voted in by the tenants and are responsible for representing the interest of the other owners. still a board package, but it is far more simple and requires less documentation. The condo board has what is referred to as “a right of first refusal,” in which they have the ability to purchase the apartment from under you. This rarely ever happens. Condos also require less money down (as low as 10%) and you are able to sublet from day one. This flexibility makes them a top choice among investors, foreign buyers and parents purchasing for their children.

COOPERATIVE

Co-ops account for approximately 50% of Manhattan’s housing inventory.

Unlike a condos or single family homes, which are defined as real property, individual co-op units are not considered real property. Think of co-ops as a nonprofit corporations, where buyers and sellers exchange shares in the corporation. The amount of shares allotted for each unit depends on several factors which include size, location relative to the building, and overall desirability. Along with the shares, a proprietary lease is issued and remains active for the duration of owners residency

Much like a corporation, co-ops appoint a board of directors to represent the interest of the shareholders or tenants. The board is responsible for establishing, enforcing, and changing the by laws and house rules. approval process for co-op buildings is a very intensive one that requires a whole package of documents. This package is referred to as a board package and includes all of your financial information, reference letters, and the application itself. This package is then reviewed by the board of trustees or board, who are internally elected officials to represent the owners’ best interests. If they consider you suitable to live in their building (totally up to their discretion), they will arrange an interview. During the interview, the board reviews your board package and clarifies any questions they may have about it or yourself. After this interview, they can again choose to approve or deny you without reason. Once purchased, the board dictates the rules of the building as it pertains to renovations, sublet policy, and who you ultimately sell the apartment to.

This all may sound daunting and scary, but there are also big pros to coops. First, this advanced screening process helps to make sure your neighbors have been properly vetted to avoid anonymous or financially unqualified owners. After all, someone has to cover the buildings operating costs if your neighbor can’t. Secondly and most importantly for most, is the significant difference in pricing. With restrictions, come discounts and for co-ops it’s about 20-25% when compared to those of similar condominiums. In a city where your dollar doesn’t afford you much, that could very well be all the difference.